Attacking Rust for Fun and Profit

Update

As mentioned in the original post, it’s been a while since I attempted any stack smashing, and I did something horribly wrong!

Here’s some more apples-to-apples Rust/C:

fn main() {

let local = "hello, world";

}

The pointer to the string is circled in red, and the return address is in blue. This indicates that even a non-mutable &str is allocated on the heap, making a buffer overflow a less viable attack.

int main ( int argc, char **argv ) {

char buf[100];

strcpy(buf, "hello, world\0");

return 0;

}

The “hello, world” string is circled in red, and the return address is in blue. You can see that if an attacker continued to write past the bounds of the string, it would be easy to overwrite the return address.

So, Rust pushes things to the stack the same way that C does (which is actually a relief to me, because I was really confused about how/why/what was happening). However, even an unmodifiable &str is still allocated on the heap, making stack smashing significantly more difficult.

Motivation

I’ve recently been looking into the usage of unsafe code in Rust programs (unsafe unicorn). I was curious about what happens when you use a C-style for loop in Rust.

Considering the following two code snippets:

let x = vec!(1,2,3);

for i in x {

println!("{}", i);

}

/// outputs:

/// 1

/// 2

/// 3

let x = vec!(1,2,3);

for i in 0..4 {

println!("{}", x[i]);

}

/// outputs

/// 1

/// 2

/// 3

/// thread 'main' panicked at 'index out of bounds: the len is 3 but the index is 3', ...

It turns out that in the implementation of slice, bounds checking is on by default. The function slice_index_len_fail can be called from index and index_mut. In order to avoid this, there would have to be a custom implementation of SliceIndex<T>, and I can’t think of a decent reason why this would happen (if you can, let me know).

After a while, I decided that safe Rust would (rightly) prevent ‘traditional’ overflows, even in non-idiomatic Rust. Therefore, I was going to have to do terrible things and abuse unsafe.

I don’t look at assembly a ton–let me know if I’ve done something horribly, horribly wrong here.

Some of this post is general playing around to see what Rust looks like in gdb, and some of this is actually attempting a contrived (stack) buffer overflow.

Buffer Overflows

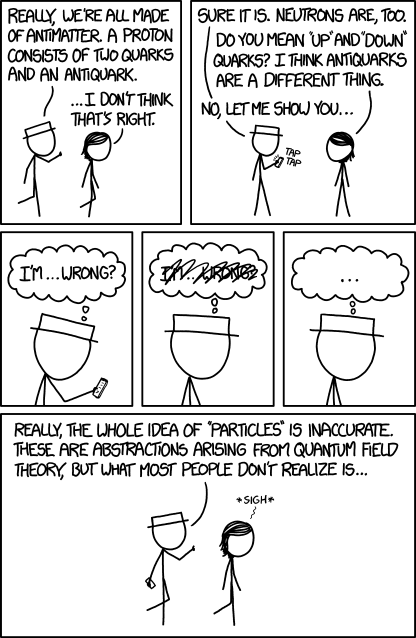

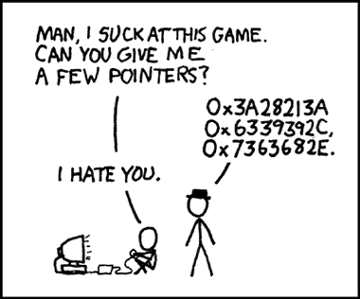

This post assumes some familiarity with buffer overflows and assembly. If you don’t know what these are, I recommend:

Using GDB with Rust

I use a Mac, but I prefer gdb to lldb, so I followed the instructions here. I still had to run with sudo, and I’m pretty sure that’s because of the way I codesigned gdb.

I used rust-gdb, which enables pretty-printing. Rustup installs it by default, so you should be good to go. When running it, point rust-gdb at the binary in target/debug/deps/<crate>-xxx–if you use the binary in target/debug/<crate>, gdb won’t be able to load symbols. It will still work, but you won’t be able to run commands like info locals or p x. You also won’t be able to step through lines of code, although next instruction does work.

All of the assembly I’ll be referencing is in x86 AT&T syntax (instr src dest).

Setting breakpoints

Set breakpoints just how you normally would:

b do_bad_thingsb mainrbreak src/main.rs:.: breaks on all functions in main- for some reason, this would only work for me after I manually broke on a function in main.rs

Resources

Diving In

#[no_mangle]

pub fn chain() {

let x = 3;

let y = 4;

let z = x + y;

chain1()

}

#[no_mangle]

pub fn chain1() {

chain2()

}

#[no_mangle]

pub fn chain2() {

let x = 3;

let y = 4;

let z = x + y;

chain3()

}

#[no_mangle]

pub fn chain3() {

chain4()

}

#[no_mangle]

pub fn chain4() {

// put some temp vars on the stack

let x = 3;

let y = 4;

let z = x + y;

println!("{}", z);

}

pub fn main() {

chain();

}

I wrote a very simple program to look at how Rust allocates memory with the stack. I chained 5 functions together and called the first from main. In gdb, I set breakpoints on each function so I could look at the call stack, then within some functions, I created local variables.

main

First, gdb breaks at main.

(gdb) info frame

Stack level 0, frame at 0x7fff5fbffa80:

rip = 0x1000032b2 in for_test::main (src/main.rs:65); saved rip = 0x100030ead

source language rust.

Arglist at 0x7fff5fbffa70, args:

Locals at 0x7fff5fbffa70, Previous frame's sp is 0x7fff5fbffa80

Saved registers:

rbp at 0x7fff5fbffa70, rip at 0x7fff5fbffa78

(gdb) x 0x100030ead

0x100030ead <panic_unwind::__rust_maybe_catch_panic+29>: 0x8348d889

The top of the frame is at 0x7fff5fbffa80, the bottom is at 0x7fff5fbffa70 and the return instruction pointer is at 0x7fff5fbffa78. If we look at this address, we see 0x7fff5fbffa78: 0x00030ead 0x00000001. What’s happening here is that the main function returns to maybe_catch_panic. You can also see this address in the “saved rip” spot. Another thing to notice is that there’s (yet another) rip = 0x1000032b2. This is the address for the main function, so a function called from main will have this set as their saved rip.

The first thing that I noticed is how small the stack for each function is–it’s only 2 addresses:

| address | |

|---|---|

| 0x7fff5fbffa80 | top of frame |

| 0x7fff5fbffa78 | rip |

| 0x7fff5fbffa70 | rbp/arglist/locals. |

Let’s compare this to a stack setup in C:

void bar(char * p) {

char buf[100];

strcpy(buf, p);

}

When you call a function in C, the argument is pushed to the stack. Then, when you allocate buf, it’s allocated locally (i.e. on the stack, not the heap). This pushes the stack pointer down 100 bytes (stack grows down). This means that the end of the 100 byte buffer immediately precedes the stack pointer, which in turn immediately precedes the return instruction pointer.

| lower memory addresses | |

|---|---|

| … | |

| 100 byte buffer | |

| rsp | |

| rip | |

| p |

At this point, it should be clear that a Rust stack looks very different than a C stack. The C stack has to fit all of the local variables. Moreover, those local variables, including things like strings, are allocated right before the return instruction pointer, so if you can overwrite the buffer, you can set that return pointer to anything you’d like (say, some arbitrary code you wrote earlier in the buffer?).

Local variables

If Rust doesn’t put the local variables on the stack like C, where does it put them?

To answer this, we’ll look at the chain* functions. For brevity, I’ll only be using the last 2 bytes of the addresses (prefix 0x7fff6fb)

| function | address | register | |

|---|---|---|---|

| main | 0xfa80 | top of frame | |

| 0xfa78 | rip | ||

| 0xfa70 | rbp | ||

| chain | 0xf9c0 | top of frame | |

| 0xf9b8 | rip | ||

| 0xf9b0 | rbp | ||

| chain1 | 0xf9b0 | top of frame | |

| 0xf9a8 | rip | ||

| 0xf9a0 | rbp | ||

| chain2 | 0xf9a0 | top of frame | |

| 0xf998 | rip | ||

| 0xf990 | rbp | ||

| chain3 | 0xf990 | top of frame | |

| 0xf988 | rip | ||

| 0xf980 | rbp | ||

| chain4 | 0xf980 | top of frame | |

| 0xf978 | rip | ||

| 0xf970 | rbp |

The functions chain, chain2, and chain4 each instantiate the same local variables x, y, z:

| function | var | address | |

|---|---|---|---|

| chain | x | 0xf9a4 | |

| y | 0xf9a8 | ||

| z | 0xf9ac | ||

| chain2 | x | 0xf974 | |

| y | 0xf978 | ||

| z | 0xf97c | ||

| chain4 | x | 0xf8e4 | |

| y | 0xf8e8 | ||

| z | 0xf8ec |

This looks the same. It’s like, why did I even bother with this post?

0x0000000100003148 <+8>: movl $0x3,-0xc(%rbp)

0x000000010000314f <+15>: movl $0x4,-0x8(%rbp)

0x0000000100003156 <+22>: mov -0xc(%rbp),%eax

0x0000000100003159 <+25>: add -0x8(%rbp),%eax

Local strings

Now, let’s consider

#[no_mangle]

pub fn local_buf() {

let mut buf = String::with_capacity(100);

buf.push('h');

buf.push_str("ello");

let buf1 = "h";

let buf2 = "meow";

}

The frame looks like this:

| 0xf9b0 | top of frame |

| 0xf9a8 | rip |

| 0xf9a0 | rbp/args/locals |

| … | |

| 0xf980 | buf2 |

| 0xf970 | buf1 |

| 0xf958 | buf |

(gdb) p &buf

$5 = (alloc::string::String *) 0x7fff5fbff958

(gdb) p buf

$6 = alloc::string::String {vec: alloc::vec::Vec<u8> {buf: alloc::raw_vec::RawVec<u8, alloc::heap::Heap> {ptr: core::ptr::Unique

<u8> {pointer: core::nonzero::NonZero<*const u8> (0x100624000 "hello\000"), _marker: core::marker::PhantomData<u8>}, cap:

100, a: alloc::heap::Heap}, len: 5}}

(gdb) p &buf.vec.buf

$7 = (alloc::raw_vec::RawVec<u8, alloc::heap::Heap> *) 0x7fff5fbff958

(gdb) x/8x &buf.vec.buf

0x7fff5fbff958: 0x00624000 0x00000001 0x00000064 0x00000000

0x7fff5fbff968: 0x00000005 0x00000000 0x0003c310 0x00000001

(gdb) x 0x100624000

0x100624000: 0x00000068

That’s…a little complicated. Let’s break it down:

- 0x7fff5fbff958: address of buf, which stores 0x100624000

- 0x100624000: the pointer to the actual data

There’s something important happening here: We aren’t necessarily pushing the actual variable to that spot–we might be pushing a pointer to a variable elsewhere in memory

- Above, in the

chainexample, the ints were pushed directly to the stack below - Here, we have both &str and String represented by pointers to the actual data

In Rust, a variable that can “grow” during execution (i.e. strings, vecs) is allocated on the heap, because it can’t be known how big it is at compile time.

(gdb) info locals

buf2 = &str {data_ptr: 0x10003c311 <str.c> "meowhello, world!\000", length: 4}

buf1 = &str {data_ptr: 0x10003c310 <str.b> "hmeowhello, world!\000", length: 1}

buf = alloc::string::String {vec: alloc::vec::Vec<u8> {buf: alloc::raw_vec::RawVec<u8, alloc::heap::Heap> {ptr:

core::ptr::Unique<u8> {pointer: core::nonzero::NonZero<*const u8> (0x100624000 "hello\000"), _marker:

core::marker::PhantomData<u8>}, cap: 100, a: alloc::heap::Heap}, len: 5}}

When we look at all of this data together, there’s another really interesting thing happening. Earlier, in the main function, I create a &str s = "hello, world", which is located at 0x10003c315. When I create buf1 and buf2, they are pushed to the memory directly before s, while the String buf is allocated to a different area of memory. Although these variables are initialized in the order s, buf1, buf2, notice that they are laid out at buf1, buf2, s instead of buf2, buf1, s as you might expect. This is (maybe) because all of the local variables for a frame are allocated (uninitialized) upon frame-entry. They are then initialized by statements within the functions, and the compiler enforces that they can’t be used until they’ve been initialized.

Buffer Overflow

#[no_mangle]

pub fn abuse_vec(v: &mut Vec<i32>) {

unsafe {

v.set_len(15);

}

overflow(&v);

}

#[no_mangle]

pub fn overflow(v: &Vec<i32>) {

for x in v.iter() {

println!("{:?}", x);

}

}

#[no_mangle]

pub fn do_bad_things(s: &str) {

unsafe {

let bad = s.get_unchecked(0..20);

println!("{:?}", bad);

}

}

fn main() {

let mut v = vec![1];

let mut s = "hello, world!"; // 68 65 6c 6c 6f 2c 20 77 6f 72 6c 64

do_bad_things(&s);

println!("{:?}", s);

abuse_vec(&mut v);

overflow(&v);

}

I don’t have ASLR turned on, so everything is in the same places in memory between builds. First, consider attempting to abuse v to overwrite the return instruction pointer–v is located at 0x100616008 and we would need to overwrite the memory at either 0x7fff5fbff9b8 (location of return instruction pointer) or 0x10000710b (location of the function we’re returning to–not precisely a stack buffer overflow, but oh well) in order to take control of the program’s execution.

(gdb) info frame

Stack level 0, frame at 0x7fff5fbff9c0:

rip = 0x100006ad4 in for_test::abuse_vec (src/main.rs:10); saved rip = 0x10000710b

called by frame at 0x7fff5fbffa80

source language rust.

Arglist at 0x7fff5fbff9b0, args: v=0x7fff5fbff9d8

Locals at 0x7fff5fbff9b0, Previous frame's sp is 0x7fff5fbff9c0

Saved registers:

rbp at 0x7fff5fbff9b0, rip at 0x7fff5fbff9b8

(gdb) p v

$4 = (alloc::vec::Vec<i32> *) 0x7fff5fbff9d8

(gdb) p &v

$5 = (alloc::vec::Vec<i32> **) 0x7fff5fbff9a8

(gdb) x/2x 0x7fff5fbff9d8

0x7fff5fbff9d8: 0x00616008 0x00000001

(gdb) x 0x100616008

0x100616008: 0x00000001

This means that the question is: can a buffer at 0x100616008 overwrite memory at 0x7fff5fbff9b8? The stack grows down, so objects pushed to the stack later have lower memory addresses. 0x100616008 is a (much) lower memory address than 0x7fff5fbff9b8. In theory, we could overwrite this, but that is a lot of memory (if my calculator is right: 17591312306998 bytes) to write, and the chances of it working don’t seem high to me.

I did try to set the length of the vector to something absurd to see what would happen:

#[no_mangle]

pub fn abuse_vec(v: &mut Vec<i32>) {

unsafe {

v.set_len(794079);

}

v[794077] = 0x00006ae4;

v[794077] = 0x00000001;

overflow(&v);

}

(gdb) info frame

Stack level 0, frame at 0x7fff5fbff950:

rip = 0x1000068b3 in for_test::abuse_vec (src/main.rs:5); saved rip = 0x100006e15

called by frame at 0x7fff5fbffa80

source language rust.

Arglist at 0x7fff5fbff940, args: v=0x7fff5fbff978

Locals at 0x7fff5fbff940, Previous frame's sp is 0x7fff5fbff950

Saved registers:

rbp at 0x7fff5fbff940, rip at 0x7fff5fbff948

(gdb) x/2x 0x7fff5fbff948

0x7fff5fbff948: 0x00006e15 0x00000001

(gdb) n

7 v.set_len(794079);

(gdb)

10 v[794077] = 0x00006ae4;

(gdb)

Thread 2 received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x00000001000068e3 in for_test::abuse_vec (v=0x7fff5fbff978) at src/main.rs:10

10 v[794077] = 0x00006ae4;

(gdb) x/2x 0x7fff5fbff948

0x7fff5fbff948: 0x00006e15 0x00000001

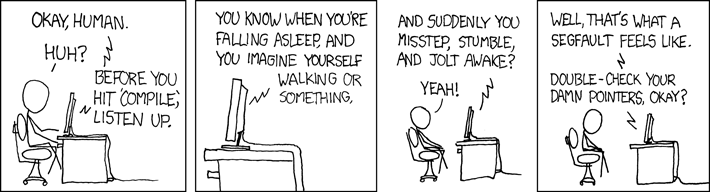

S-s-s-s-s-s-s-segfault!!!!!

What about a buffer at 0x100616008 overwriting memory at 0x10000710b? The buffer is at a higher memory address, meaning that it would need to write backwards. Due to type safety, this would be difficult–indices need to be usize.

do_bad_things

I played around with a string, but I couldn’t quite manage to make get_unchecked_mut to compile. The variable s is located at 0x7fff5fbff890, but the data is at 0x10003c195, so this approach suffers from the same problems.

(gdb) p &s

$1 = (&str *) 0x7fff5fbff890

(gdb) p s

$2 = &str {data_ptr: 0x10003c195 <str.g> "hello, world!\000", length: 13}

(gdb) x/2x 0x7fff5fbff890

0x7fff5fbff890: 0x0003c195 0x00000001

Is a buffer overflow possible?

Not really.

Buffer overflows rely on the fact that the buffer is pushed to the stack before the return instruction pointer (and, of course, a missing bounds check). Rust sticks bounds checks all over the place, but even if you bypass those, either through abuse of unsafe or custom types that skip bounds checks, the stack memory layout makes it really difficult (if not impossible). A key protection is that Rust doesn’t ever (?) put a ‘growable’ object like a &str/String/Vec on the stack. This means that an exploit would need to overwrite very large amounts of data, likely causing a crash in other ways before taking control of the program.

This supports Rust’s memory safety claims, as well as providing a fun way to play with rust-gdb.

Further work

I think it would be really neat to look at how #[repr(C)] looks in memory. I also want to look at some crypto libraries to see how data is sanitized, etc. Overall, I think data leakage in Rust is likely a more reasonable exploit approach as opposed to modifying control.

I hope to try some other classic attacks on Rust to see what happens.